Disclaimer: This post/article/blog is for informational purposes only and is not a substitute for professional mental health advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always seek the advice of qualified health providers with any questions you may have regarding mental health concerns.

Infographics were created by a mix of professionals and people with ADHD and selected by Katie to reflect what she has experienced personally and professionally.

Table of Contents

ADHD 101

- Introduction: Redefining ADHD

- The Brain and ADHD: A Neuroscientific Perspective

- Executive Functions: The Brain's Control Center

- Surprising Severity of Impact

- ADHD as Self-Regulation Deficit Disorder

- Beyond Surface Symptoms

- Implications for Treatment and Management

- Conclusion: A Paradigm Shift in Understanding ADHD

Hi, I'm Katie.

I’m a neurodivergent mental health counselor. I specialize in helping neurodivergent adults navigate complex intersectional identities and comorbid mental health, trauma, or substance use.

This blog is shaped by my own education and experiences as a therapist. It's not a definitive resource, not a textbook to be quoted or a manual to be followed. Instead, it's an offering—by someone with an unusual mix of perspectives and skills. Someone who has spent too long living in and witnessing the growing disconnect between people and the cost of harmful misunderstandings.

Introduction: Redefining ADHD

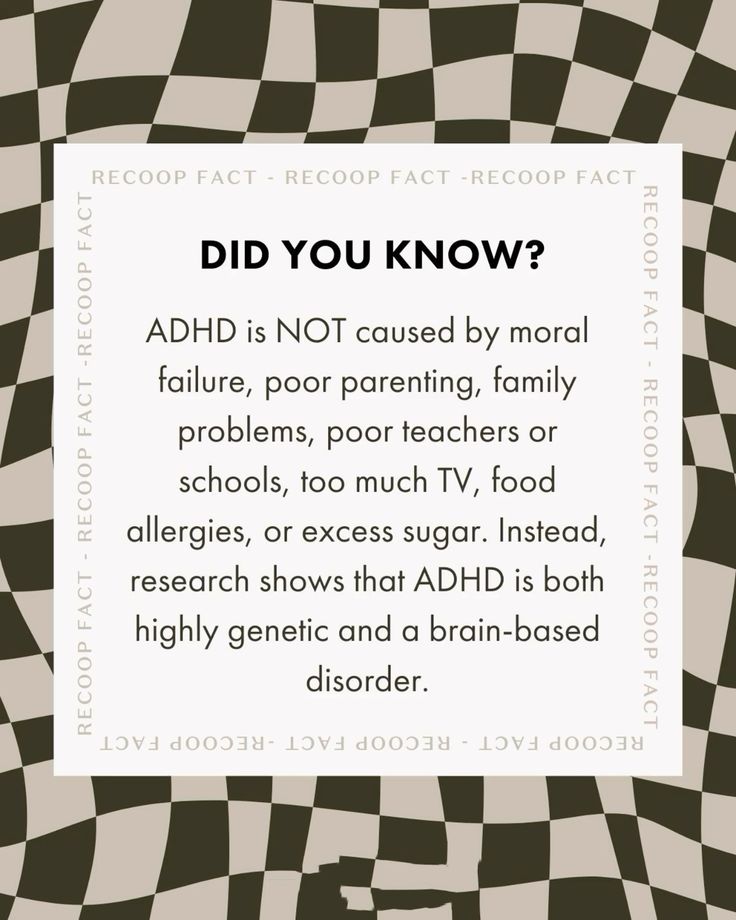

For decades, Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) has been widely mischaracterized and oversimplified as merely a disorder of poor attention span or an inability to stay focused. However, this restrictive view fails to capture the true complexity and breadth of challenges faced by those with ADHD.

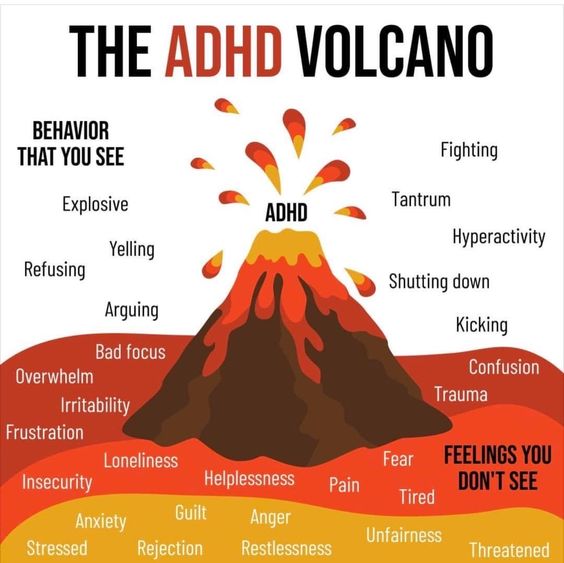

Not only does the oversimplification fail to communicate the patterns of behaviors visible to the people around someone with ADHD, but it also fails to communicate what is happening inside the person’s brain, emotions, and body.

As Dr. Russell Barkley, a leading expert in ADHD research, emphatically stated, "The name is trivial relative to what is actually going on in the brain in its neuropsychological functioning...ADHD gets no respect." This powerful statement underscores the urgent need for a more comprehensive understanding of ADHD.

The latest research points to ADHD being fundamentally a disorder stemming from disruptions in the brain's self-regulatory control systems - the intricate neural circuitry governing "executive functions." To fully grasp the implications of this perspective, we need to delve deeper into the neuroscience behind ADHD and the concept of executive functions.

The Brain and ADHD: A Neuroscientific Perspective

To understand ADHD more comprehensively, it's crucial to examine its neurological underpinnings. ADHD is not simply a behavioral disorder; it's a complex neurodevelopmental condition that affects brain structure, function, and connectivity.

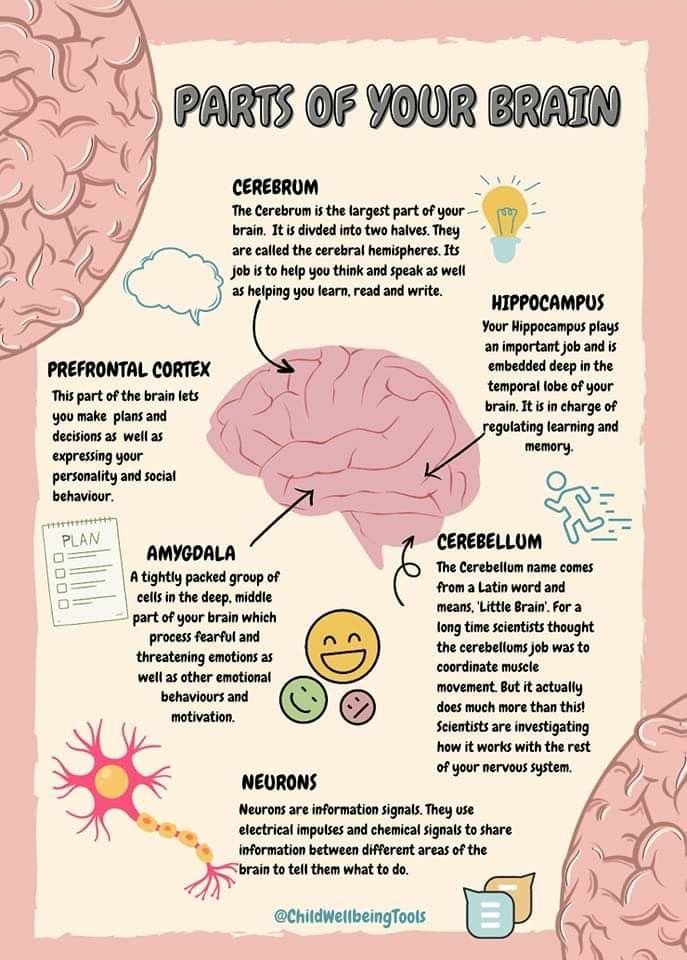

Neuroanatomical Differences

Research using neuroimaging techniques has revealed several key differences in the brains of individuals with ADHD:

- Prefrontal Cortex: This region, responsible for higher-order cognitive functions, often shows reduced volume and activity in people with ADHD.

- Basal Ganglia: These structures, involved in motor control and learning, may be smaller in individuals with ADHD.

- Corpus Callosum: The bundle of fibers connecting the two hemispheres of the brain can be smaller in ADHD, potentially affecting inter-hemispheric communication.

- Cerebellum: This area, traditionally associated with motor coordination but also involved in cognitive functions, may show reduced volume in ADHD.

Neurotransmitter Imbalances

ADHD is also associated with imbalances in key neurotransmitters:

- Dopamine: Often referred to as the "reward neurotransmitter," dopamine plays a crucial role in motivation, attention, and impulse control. ADHD is linked to lower dopamine levels or reduced dopamine receptor sensitivity.

- Norepinephrine: This neurotransmitter is involved in alertness and attention. Imbalances in norepinephrine are thought to contribute to ADHD symptoms.

Brain Networks and Connectivity

Recent research has shifted focus from isolated brain regions to the connectivity between different areas. In ADHD, there appear to be alterations in several key brain networks:

- Default Mode Network (DMN): This network, active when the mind is wandering, may be overactive in ADHD, potentially contributing to inattention.

- Cognitive Control Network: This network, crucial for goal-directed behavior, may show reduced activity and connectivity in ADHD.

- Reward Network: Alterations in this network may contribute to motivational issues and difficulty delaying gratification.

Understanding these neurological differences helps explain why ADHD impacts far more than just attention. It affects a wide range of cognitive processes and behaviors, which are collectively managed by the brain's executive functions.

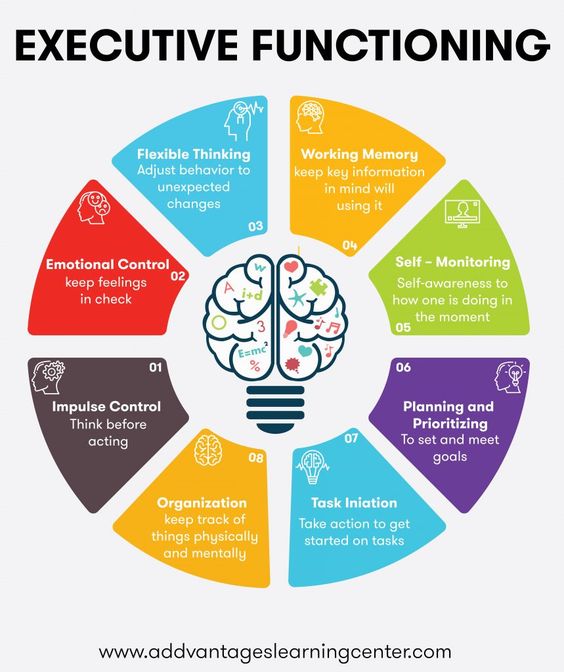

Executive Functions: The Brain's Control Center

Executive functions represent an interconnected set of high-level cognitive abilities that allow us to regulate our thoughts, emotions, and actions in the pursuit of goals. They are often described as the "conductor" of the brain's orchestra, coordinating and managing various cognitive processes.

Core Executive Functions

- Working Memory: This is the ability to hold information in mind and manipulate it over short periods. It's crucial for following instructions, solving multi-step problems, and keeping track of complex tasks.

- Inhibition: Also known as inhibitory control, this function allows us to suppress prepotent responses and impulses. It's essential for self-control, appropriate social behavior, and focused attention.

- Cognitive Flexibility: Also called set-shifting, this is the capacity to switch between different tasks or mental sets. It's important for adapting to new situations and problem-solving.

- Planning and Organization: This involves the ability to create and execute multi-step plans, manage time effectively, and keep materials and information organized.

- Self-Monitoring: This is the capacity to evaluate one's own performance and behavior, making adjustments as needed.

- Emotional Control: While sometimes considered separately, the ability to modulate emotional reactions is a crucial aspect of executive function.

- Initiation: This is the ability to begin a task or activity and to independently generate ideas, responses, or problem-solving strategies.

As Barkley discussed, "These supervisory cognitive skills are anchored primarily in the prefrontal regions of the brain and their extensive neural connections throughout other cortical and subcortical areas involved in attention, memory, and behavioral regulation."

ADHD and Executive Dysfunction

For individuals with ADHD, the root neuropsychological deficits appear to be in these very executive function domains - the higher-order control mechanisms that regulate, prioritize, and integrate more automatic attentional and cognitive processes.

Contradicting common misunderstandings, Barkley emphasized, "Someone with ADHD does not simply have a short 'attention span.' Rather, they have significant impairments in their ability to sustain attention purposefully overtime on tasks while working memory guides their responses."

People with ADHD struggle mightily with:

- Inhibiting impulses

- Resisting distractions

- Regulating their emotions

- Adjusting to changes

- Self-monitoring their performance

The symptoms we associate with ADHD, such as inattentiveness, hyperactive restlessness, impulsivity and procrastination, can all be traced back to deficits in these core executive functions acting as the "conductor" of cognitive abilities and self-regulated behavior.

Surprising Severity of Impact

What many find surprising is just how profoundly and pervasively these self-regulatory deficits can impair major life activities for those with ADHD. Even highly intelligent individuals may struggle with the following:

- Task Engagement: Maintaining consistent engagement on important tasks and responsibilities.

- Impulse Control: Controlling distracting urges and emotional impulses appropriately.

- Organization and Time Management: Staying organized, prioritizing effectively, and managing time.

- Decision Making: Thinking through consequences before acting rashly.

- Follow-through: Following through on commitments and meeting obligations

The root challenges are not just attentional but represent fundamental difficulties with self-directed regulation of behavior according to future goals and socially-appropriate norms. This can create massive disruptions in academic, occupational, social, and personal domains that are "unexpected given the person's intelligence," as Barkley surprisingly noted.

ADHD as Self-Regulation Deficit Disorder

It is for this very reason that Dr. Barkley, in a pioneering reconceptualization, has proposed viewing ADHD more accurately as a "self-regulation deficit disorder" or an "executive function deficit disorder (EFDD)."

This framing acknowledges that the fundamental impairment lies not with attention itself, but rather with the self-regulative abilities needed to control attention, behavior, emotions, and cognitive resources over time to achieve goals and intentions. The deficits in working memory and executive capabilities tend to be far beyond what one would expect based on one's chronological age.

Those with ADHD often struggle profoundly with:

- Sustained Attention: Inhibiting distractions and staying vigilantly on task.

- Working Memory: Holding instructions, expectations, and goals actively in mind.

- Emotional Regulation: Managing emotions and motivation toward immediate gratification.

- Self-Monitoring: Monitoring performance to adjust and problem-solve flexibly.

- Planning and Follow-through: Planning, prioritizing, and following through over time.

The ADHD brain appears to experience delays or connectivity disruptions within neural circuits governing these higher-order executive capabilities that "conduct" more basic cognitive processes.

Beyond Surface Symptoms

Looking beyond just the overt symptoms provides a richer perspective on ADHD's deeper roots in self-regulation deficits stemming from executive brain dysfunctions.

The self-regulatory challenges impact all life arenas by undermining the ability to:

- Consistently engage attention/working memory on key tasks

- Inhibit impulses and delay gratification purposefully

- Regulate emotions/motivation productively toward goals

- Self-monitor and flexibly adjust behaviors as needed

- Multitask, plan, prioritize and reliably follow through

As Barkley bluntly stated, "These effects lead to the

hallmark ADHD impairments - not just from inattentiveness, but from global dysregulation of behavior according to one's conscious intentions."

Contradicting prevailing societal misconceptions, Barkley emphasized that these self-regulation deficits are "real, they're disabling, and it's not something you can just overcome through willpower or waking up and smelling the coffee."

Implications for Treatment and Management

By understanding ADHD as fundamentally an executive function and self-regulation disorder, we can reframe the challenges and expand management options through:

- Medications: Targeting executive neural networks rather than just attention.

- Behavioral Strategies: Developing compensation strategies for regulating cognition.

- Environmental Support: Creating scaffolding and supports to enhance self-control.

Rather than simply trying to improve stimulus-response attentional abilities alone, this model calls for interventions regulating, prioritizing, and smoothly coordinating the cognitive subsystems disrupted by ADHD's self-regulatory deficits.

Medication Approaches- Stimulant medications like methylphenidate (Ritalin, Concerta) and amphetamines (Adderall, Vyvanse) remain the first-line pharmacological treatments for ADHD. These medications work primarily by increasing dopamine and norepinephrine levels in the brain, which can enhance executive function capabilities.

The goal of medication in this framework is not just to improve attention but to enhance overall self-regulatory capacity across multiple domains of executive function.

Behavioral Strategies- Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) adapted for ADHD and Executive Functioning Coaching can be highly effective in developing compensatory strategies for executive function deficits. Some key areas of focus include:

- Time Management: Using tools like calendars, timers, and reminders to externalize time awareness.

- Task Initiation: Breaking tasks into smaller, more manageable steps and using implementation intentions.

- Emotional Regulation: Practicing mindfulness and cognitive reframing techniques.

- Organizational Skills: Implementing consistent systems for organizing physical and digital spaces.

- Self-Monitoring: Using self-rating scales and regular check-ins to increase self-awareness.

Environmental Supports- Creating an environment that supports executive function can significantly reduce the impact of ADHD. This might include:

- Minimizing Distractions: Creating a dedicated workspace with minimal visual and auditory distractions.

- Using Visual Aids: Employing whiteboards, sticky notes, and visual schedules to externalize information.

- Leveraging Technology: Using apps and digital tools designed to support executive functions.

- Establishing Routines: Creating consistent daily routines to reduce cognitive load.

- Social Support: Enlisting the help of family, friends, or coaches to provide external accountability and support.

Accommodations at Work or at School: To leverage strengths and provide support based neurological and developmental differences.

Conclusion: A Paradigm Shift in Understanding ADHD

Reframing ADHD as a disorder of executive function and self-regulation represents a significant paradigm shift. It moves us away from the oversimplified view of ADHD as merely an attention problem and towards a more comprehensive understanding of the complex neurological and behavioral challenges faced by individuals with ADHD.

This new perspective has profound implications for diagnosis, treatment, and societal understanding of ADHD:

- Diagnosis: Assessment should focus not just on attention and hyperactivity, but on a broad range of executive function capabilities across different life domains.

- Treatment: Interventions should target the underlying executive function deficits, not just surface-level symptoms of inattention or hyperactivity.

- Education: Schools need to understand that students with ADHD aren't just "not paying attention," but are struggling with fundamental self-regulatory challenges that impact all aspects of learning and behavior.

- Workplace Accommodations: Employers should recognize that employees with ADHD may need support in areas beyond just staying focused, such as time management, organization, and emotional regulation.

- Social Understanding: By recognizing ADHD as a disorder of self-regulation, we can foster greater empathy and support for individuals who struggle with these invisible but profound challenges.

As our understanding of ADHD continues to evolve, it's crucial that we update our language, our conceptual models, and our approaches to support. By recognizing ADHD as a complex disorder of executive function and self-regulation, we can develop more effective, compassionate, and comprehensive ways to support individuals with ADHD in reaching their full potential.

In the words of Dr. Barkley, "ADHD is not a simple problem of being distractible. It is, instead, a complex disorder of the brain's executive functions and self-regulation that impacts virtually every domain of daily life activities." It's time for our understanding and treatment of ADHD to reflect this complexity

We welcome all people, regardless of race, ethnicity, age, religion, gender identity, sexual identity, relationship status, body composition, or disability. We pledge to provide a safe space for our team and our clients.